Project Overview

The Moravian Lives project has been running since 2015. An ongoing collaboration between the Centre for Critical Heritage Studies at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden and Bucknell University in the USA, the project initially sought to visualize through a geospatial interface the metadata associated with over 60,000 “ego-documents.” These manuscripts are by or about members of the Moravian Church, known in Germany as the “Brüdergemeine” or “Herrnhuter” and worldwide as the Unity of the Brethren in whose main archives in Herrnhut and Bethlehem, these documents lie.

The initial stage of the project focussed on the spatial visualization of the archival metadata, allowing the user to pinpoint the birth and death places of each author in the database and also track the movement of that author through geographic space. Built-in filters also allowed the user to refine searches by gender, time period, and source archive. If a user wishes to visualize the dispersal or movement of women, for example, in a specific date range, the results show the record and also, where available, a link to the original archival document. Members of the team have worked closely with archivists in Bethlehem, PA and London and Fulneck in the UK to digitize, upload, and present the digital artefacts in a transcription environment that keeps the two types of files linked.

We pose the research question: when encoding these archival documents, can developing ontologies of work vs office help us understand important distinctions in the definition of work?

How can text encoding lead us to insights about members’ activities in the Moravian religious settlement of Fulneck in the 18th century at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution?

Transcribing the Memoirs

Dr. Mike McGuire designed our custom-built transcription desk, which presents a digital text of a document, where viewers can read the transcribed memoirs online and also create custom corpora to be further marked up. The transcription desk uses a Scripto plugin and WordPress frame, and displays images that are served by Bucknell, as well as the Herrnhut archives and the Gothenburg Center for DH. Hand-typed transcriptions are then saved in a MediaWiki instance hosted at Bucknell.

In 2018, with funding from the newly established Hildreth-Mirza Humanities Center at Bucknell, two undergraduate students were hired as student researchers and trained as transcribers of the English-language memoirs. One student, Carly Masonheimer, was awarded a scholarship to attend the German script seminar at the Moravian Archives in Bethlehem, PA to train her in the reading of archaic German Script, the hand in which the majority of the memoirs are written.

In 2019 we started using the HTR (handwritten text recognition) platform Transkribus as part of our workflow. Social Sciences Librarian Carrie Pirmann has led this branch of the project. Digital images from the corpus were batch uploaded to Transkribus’ servers and diplomatic transcriptions for those documents were input into Transkribus to create HTR models specific to the project’s materials. With adequate training data and refinement of models, we have been able to create models that yield a CER (character error rate) of between 5-10% against untranscribed memoirs. These resultant transcriptions still need to be checked by humans, a job done by the PI, Katie Faull, Carrie, and student researchers Carly Masonheimer and Jess Hom. Finalized transcriptions are exported from Transkribus in XML format, which are then used in the encoding phase of the project. We also export TXT and keyword searchable PDF versions for ease of reading.

Encoding the Memoirs

The methodology employed for this investigation of Working Moravian Lives is rooted in TEI-encoding of specific entities within these ego-documents in order to build up a personography, a gazetteer, and a sentiment dictionary of Early Modern English Evangelism. Such encoding of entities allows the team to ask questions of the texts about the relationships between sentiment and work, sentiment and place, sentiment and people. Digital Scholarship Coordinator Dr. Diane Jakacki has led this branch of the project and works closely with undergraduate Presidential Fellow Justin Schaumberger to engage in semantic markup and develop our schema.

Moravian Lives has been encoding memoirs to capture people, places, organizations, and concepts of labour and emotion. From the transcribed memoirs, Carrie Pirmann and Justin Schaumberger developed a “personography” – a comprehensive list of information about the Fulneck Moravian people for whom we have gathered memoirs, as well as those referred to in these memoirs. In the process of close-reading the memoirs, while he encodes them, Justin elicits information about these people that will in turn feed into a comprehensive data model – revealing relationships between people, tracing their journeys (physical and spiritual), occupations, church offices, their experiences, affiliations, and emotions. The idea of personographies is not new in the Digital Humanities, but the interlinked data that we have been gathering is unusual.

In order to balance our internal needs with best practices, we regularly consult the TEI guidelines carefully while at the same developing a comprehensive and highly customized schema that captures and supports the detail within the Fulneck memoirs. This in turn has allowed us to cross-reference information about occupations and offices.

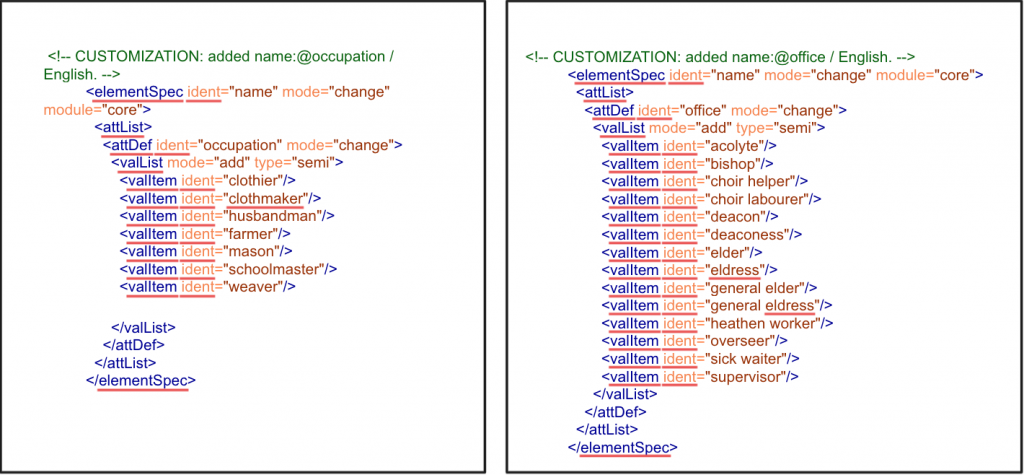

In the process of building a schema that responds to the memoirs, Justin has focused in particular on distinguishing occupations (clothmaker, farmer, mason) from church offices (choir helper, sick waiter). This is a vital distinction in the discussion of Moravian attitudes to work. In the schema, this differentiation is accounted for by customizing the “name” element with attributes “occupation” and “office”.

Occupations and Offices

As the memoirs were scraped and semantically encoded, the Moravian Lives project team began building out unique identifiers for the instances of occupations and offices captured. The instance of work was then encoded with the proper unique identifier so that they could be linked to other instances of the same type of work in the future. In addition, unique identifiers are being used in the process of building ontologies for occupations and offices to further define the specific instances of work. Within the ontologies, offices and occupations will be given definitions and can be linked to other types of related work within the ontology. The definitions for each ontological entry can either come from the Moravian Lives encoding team or a different source in order to give the most accurate definition for the term. The responsible party will be captured within the definition in case any discrepancies arise in the future. Additionally, the existence of an ontology of the work allows for the opportunity for collaboration with other projects. Within the given entry, an instance of work can be linked to a term that exists in another corpus such as Wikidata.

Recognizing the complexities of work, we have decided to split it into two categories. We defined an office as labour dealing with the Moravian Church, which is typically unpaid (ie: Warden or Bishop). Occupation is labour in which an individual is typically compensated (i.e. Farmer). Each instance of work is also given a definition from the OED along with its unique identifier. In the process of building a schema that responds to the memoirs, Justin has focused in particular on distinguishing occupations (clothmaker, farmer, mason) from church offices (choir helper, sick waiter). This is a vital distinction in the discussion of Moravian attitudes to work. In the schema, this differentiation is accounted for by <name occupation=“”></name> and <name office=“”></name>.

While encoding the memoirs, we are attempting to be as specific with the work titles. For instance, we are giving Single Sisters’ warden a different unique identifier than congregation warden. In the future, we are going to try to connect the different occupations and offices that are subtypes of one another. So in single sisters’ warden and congregation warden example, both of these would be subtypes of warden.

Once the office and occupation distinction was made, the Moravian Lives project team chose to further separate the offices within the Moravian Church based on the choir they were in. For instance, the office of warden was separated into Single Sisters’ warden, Single Brethren’s warden, Congregation warden, etc. This allows for more interesting queries to be performed that look at the relationship between gender and work. Additionally, since the ontology can link related offices together, the same position in different choirs can still be connected and be queried as such.

James Charlesworth serves as a good example of why this distinction is necessary. Charlesworth initially was a warden for the Single Brethren’s choir in 1744 as detailed in his memoir. In 1754, Charlesworth was given a new position as the warden for the entire congregation in Yorkshire. If both positions were tagged as warden, there would be no way to discover this change in position of Charlesworth. Instead, it would appear he only had the same office for 11 years.

Developing a Schema

Developing our own schema allows for a constrained vocabulary so that all encoding uses the same language. As there are many eyes that look at and encode the documents, a common vocabulary allows for a smooth transition in the workflow and also makes possible the creation of new categories for further distinction, like with offices and occupations.

Using the custom schema, a list of Moravian “events” (e.g. reception, communion) and “life” events (birth, death, marriage) has been developed in German and English. This list is constantly being added to in order to satisfy events listed in the memoirs. Another benefit of the custom schema is it gives us the ability to create sameAs relationships across different languages. In the schema, we can specify that a given attribute in English is the same as a given attribute in German or another language. This is important because the memoirs are transcribed in multiple different languages, and creating a schema that limited encoding to only one language would be a hindrance to the project as a whole.

Additionally, all the emotions, dates, people, etc that are linked to a given event have also been encoded. Here, the event type itself is encoded as well as person, place, date information. This idea of capturing all the possible information in an event is especially significant for the encoding of emotions, which are frequently attached to Moravian events.

Searching Fulneck Lives

The newest feature of the Moravian Lives project is a faceted, fully-searchable database that allows users to make queries about Moravians associated with the Fulneck congregation. This custom-designed application is built using a NoSQL database, which allows us to accommodate searching in more flexible ways. The database will continue to be expanded so that new types and sets of data will be added in future and users can search by place, occupations, events, choirs, as well as additional congregations. Eventually, this data will also support spatial and network visualizations.